THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

V. The Vlachs of Moschopolis and the surrounding area

3.2. Moschopolis, the glory days, 1700–1769

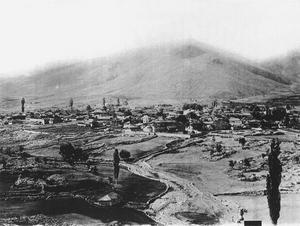

In the eighteenth century, Moschopolis and the local Vlach settlements attained the peak of their development and prosperity; but this was accompanied by a number of insuperable problems, which eventually led to disaster and decay. The foundations of this glorious period had been laid in the seventeenth century, when Moschopolis was growing, not only demographically, but also economically and culturally. One indication of this development was the construction of the Monastery of St John the Baptist in around 1630. Some studies describe Moschopolis as the second largest town in the Ottoman Balkans after Constantinople, though this is in fact unlikely if we consider such cities as Thessaloniki and Adrianople. Nonetheless, it must have been the only town of its size with an exclusively Christian population. It had six large, organised districts and possibly more than seventy churches, though this is probably an exaggerated figure. Although the various sources frequently disagree about the precise number of houses and residents, in around 1760 the town reportedly had somewhere between 20,000 and 70,000 inhabitants and perhaps as many as 12,000 households. These figures seem unlikely for the period, especially in view of the picture we have of Moschopolis from 1769 onwards. The town covered a vast area and occupied much of the now bare plateau and the low slopes round about. It may not be so rash, after all, to accept that the population reached 40,000 in its most prosperous period.[1]

In the eighteenth century, Moschopolis and the local Vlach settlements attained the peak of their development and prosperity; but this was accompanied by a number of insuperable problems, which eventually led to disaster and decay. The foundations of this glorious period had been laid in the seventeenth century, when Moschopolis was growing, not only demographically, but also economically and culturally. One indication of this development was the construction of the Monastery of St John the Baptist in around 1630. Some studies describe Moschopolis as the second largest town in the Ottoman Balkans after Constantinople, though this is in fact unlikely if we consider such cities as Thessaloniki and Adrianople. Nonetheless, it must have been the only town of its size with an exclusively Christian population. It had six large, organised districts and possibly more than seventy churches, though this is probably an exaggerated figure. Although the various sources frequently disagree about the precise number of houses and residents, in around 1760 the town reportedly had somewhere between 20,000 and 70,000 inhabitants and perhaps as many as 12,000 households. These figures seem unlikely for the period, especially in view of the picture we have of Moschopolis from 1769 onwards. The town covered a vast area and occupied much of the now bare plateau and the low slopes round about. It may not be so rash, after all, to accept that the population reached 40,000 in its most prosperous period.[1]

Not only Moschopolis, but the surrounding Vlach villages also amassed a large number of inhabitants for that time. Although the figures offered by the various studies seem exaggerated, Niçë, Llëngë, Grabovë, Shipckë, and the Albanian-speaking Vithkuq must have been large and vigorous market towns following close on the heels of the progressive Moschopolis.[2] Their natural locations protected them from the pressures of Arnaut feudal lords both great and small, and they became vigorous local markets for the surrounding population, maintaining independent relations with the commercial centres of the Balkans and Europe.[3] Each of these local settlements may eventually have had a population of between 5,000 and 10,000.

Socially, Moschopolis was divided into three basic classes. At the top were the notables, the oldest, powerful families. The wealthy and frequently immigrant merchants and craftsmen made up the very vigorous middle class. And at the bottom of the pyramid were the simple labourers, artisans, muleteers, woodcutters, shepherds, and farmers. As far as possible, the administration of the town was in the hands of the inhabitants themselves, mainly the members of the upper and middle classes. Each district appointed an elder, and so at first the community council had six members, one of whom acted as chairman. The chairman was elected by vote and the result ratified by a firman. Later on, there were twelve councillors, when a kocabasi was included from each district, charged with collecting the taxes. But apart from the community council, an active role in the town’s public affairs was also played by the powerful guilds, organised professional bodies which seem to have numbered between thirteen and seventeen, though there are reports of even more. The town’s security was guarded by a small garrison of Arnauts, who were required to defend the surrounding mountain passes leading to and from Moschopolis and ensure free passage for transport and trade.[4]

Moschopolis drew its wealth and strength from commerce and the various craft trades. As in the case of other well-developed Vlach communities (such as Metsovo, Syrrako, and Kalarites), progress and development were primarily based on stockbreeding. But in fact Moschopolis was well in advance of the others by the seventeenth century, and it was probably Moschopolis which blazed the trail for the other Vlach and non-Vlach highland communities. Thanks to abundant raw materials and labour, the wool industry boomed. The early cottage industry in woollen goods evolved into organised light industrial production and eventually into trade in both the final products and the raw materials. By trading in their own products and amassing capital, the townsfolk gradually developed wider ranging commercial, compradorial, and light industrial activities, and the caste of the so-called pragmateftades was born (pramatefts or pramateftadz in Vlach, ‘itinerant trader’). The craftsmen organised and strengthened the institution of the guilds. There were guilds of grocers, tailors, goldsmiths, butchers, coppersmiths and ironsmiths, gunsmiths, cordwainers, and many more, and they played an important part not only in economic development and local politics, but also in cultural progress, for they reportedly paid for scholarships to cover indigent children’s education in schools both in Moschopolis and in Europe.[5]

However, the greatest economic and cultural wealth came with the development of connections with Europe and the shift towards compradorial activities. It is not unlikely that there were Moschopolitans among the merchants in the Greek Orthodox community in Venice as early as 1537. In that year, the immigrants in Venice built a Greek Orthodox church and a Greek school.[6] In the course of the seventeenth century, the Moschopolitans, via Durrës, forged close commercial relations both with Venice and Ancona and with other Italian ports on the Adriatic.[7] Enterprising merchants transported goods there from all over the central Balkans and as far away as the Danubian Principalities. And they returned not only with other merchandise or capital, but also with valuable knowledge. The merchants were followed on their voyages to Venice by young Moschopolitans wishing to study there or to serve apprenticeships with important merchants. It is interesting to note that, in 1694–1703 and 1712–16, a scholarly priest from Moschopolis named Ioannis Halkias served as director of the Flanginis Institute and preacher in the Greek Orthodox Church of St George in Venice, having previously served as parish priest to the Greek Orthodox community in Leghorn.[8] In this period, the Moschopolitans were travelling as far afield as Constantinople, not only on their own or on community business, but performing services for the Venetians.[9]

Relations with Venice continued until about 1761. During this time, quite a number of Moschopolitans registered on the municipal roll of the Greek Orthodox community of Venice and do not seem to have differed in any way from the other members. But as Venetian trade began to decline, the Moschopolitans, like other Vlach and non-Vlach merchants from various towns in Macedonia, set their sights on Central Europe, and started accompanying the numerous caravans heading north.[10] The Treaties of Passarowitz (1718) and Belgrade (1739) between the Ottoman and Habsburg Empires proved especially favourable to this new trend. Thus, from 1718 to 1774 Moschopolitans settled en masse in the Habsburg dominions. Some went as far as Warsaw in Poland and Leipzig in Germany. At first they were only men, and mainly young men, seeking opportunities for trade and/or permanent residence. Their wide and varied commercial and light industrial activities soon led them to establish colonies both in Central Europe (including Vienna, Budapest, Szentendre, Miskolc, Kecskemét, Timisoara, Novi Sad, and Zemun) and in various commercial and administrative centres in Macedonia, Thessaly, Epiros, and Albania. Enterprising Moschopolitan merchants and craftsmen also travelled to and worked at the major annual fairs in these Ottoman provinces. The travellers’ journeys, trading activities, and remittances soon nurtured even greater growth and progress.[11]

Economic prosperity paved the way for cultural development, as is evidenced by the fact that nine splendid new churches were built between 1715 and 1760. Those which are still standing are incontrovertible witnesses to the high noon of Moschopolis.[12] Even before 1700 there was an organised Greek school. The school developed along with, and met the demands of, the vigorous, progressive society that built it. The teachers were highly educated and influential, and the Moschopolitans also took care to engage outstanding scholars from elsewhere to teach there. In 1744, new subjects were added to the curriculum and the Moschopolis school became the celebrated New Academy; and in 1750, when it moved to new premises more appropriate to its fame and requirements, it was renamed the Hellenic Phrontistery. The course of study it offered was possibly one of the most advanced which a Christian could attend in the Balkans at that time, essentially making Moschopolis one of the most important centres of the Greek Enlightenment. The library was one of the largest and most splendid in the Balkan provinces in those days. Under the aegis of the New Academy, residential premises were provided to accommodate and feed students who came to attend the Moschopolis schools from all over the Balkans. Among the social institutions that came into being was the Poor Fund, a community fund whose purpose was to provide relief for the less privileged townsfolk. One of the most admirable establishments in this singular town was the printing-house, which began operating in 1720 or in 1735. It used Greek type, and was therefore the second Greek printing-house in the Ottoman Empire after that of Constantinople (1627). Many of the young Moschopolitans and the students who came from elsewhere to attend the town’s schools went on to continue their education in schools and institutions in Austria, Germany, Italy, and even Holland.[13] So Moschopolis was justly dubbed the ‘New Athens’. Apart from in Moschopolis, a strong educational tradition also developed in Vithkuq, Shipckë, and Korçë, where Greek schools were operating in the eighteenth century.[14]

It is worth noting that the influx into the market and the schools of Vlach-speaking Moschopolis of immigrants, traders, teachers, and students from all over the Balkans, who spoke Vlach, Greek, Albanian, and Bulgarian, led to the publication of two lexicons that were really quite splendid for their time. In those days, when the various nationalist movements were unknown, at least in the form in which they developed in the Balkans after the mid-nineteenth century, the enterprising, progressive Moschopolitans saw no harm, but rather practical benefit, in recording and studying the Vlach, Albanian, and Bulgarian tongues. The compiling and publication of the lexicons was intended more as an aid to the education of the various non-Greek-speaking Christians, because the education that was offered in Moschopolis (and elsewhere too) was essentially regarded as Greek. Theodoros Anastassios Kavalliotis, one of the most brilliant Moschopolitan teachers and a leading light in the Greek scholarly world, published his Protopiria (Starting out) in Vienna in 1770. It includes a 1,170-word lexicon of the simple modern Greek, Vlach, and Albanian languages.[15] Kavalliotis’s efforts were continued by one of the New Academy’s most important teachers, the priest and monk Daniil Moschopolitis, with his Introductory Teaching containing a Four-Language Lexicon of the four common dialects, namely simple Romaic [modern Greek], Moesian Vlach, Bulgarian, and Albanian, which was published or written in Moschopolis in 1764 and republished in Vienna in 1794 and 1802.[16]