THE VLACHS: METROPOLIS AND DIASPORA

IV. The Arvanitovlachs

7. The Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli (Mainland Greece)

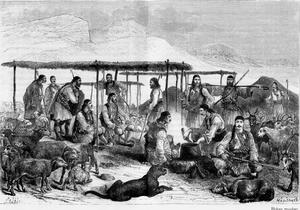

In around 1840, the large Arvanitovlach settlement at Bitsikopoulo was apparently destroyed and abandoned following raids by Arnaut brigands. Most of the families who had been living there since Ali Pasha’s time fled to the safety of the newly established Greek state, where they continued their nomadic pastoral lifestyle, moving between the Agrafa Mountains and other highland areas in Evrytania, and in Epiros too, in Ottoman territory, and the lowland areas of Xiromero in Akarnania as far as the mouth of the Aheloös. Heuzey reports that in 1856 they numbered 800 families (4,000 to 5,000 souls) and established twelve large winter settlements with between fifty and a hundred families each.[1]Between 1865 and 1870, they gradually started to establish more permanent dwellings in these winter abodes. The villages which they established at this time are now the southernmost Vlach settlements: Stratos (Sourovigli or Yannika), Ohthia (Ohtou or Payeïka), Agrambela (Dayanda), Gouriotissa (Katsarou), Paliomanina (Koutsobina), Strongylovouni (Stournari or Gakeïka), and Manina Vlizianon (Kaledzi).[2] It should be noted that the Arvanitovlachs of Roumeli have come to be generally known as Karagounides. According to an article in the periodical Pandora, in about 1856 the Arvanitovlachs of Aitolia and Akarnania numbered about 2,000 and had 100,000 sheep, which gave the Greek state what was then a considerable income of 20,000 drachmas in taxes.[3] Weigand reports that in 1888–9 there were 2,625 souls in the seven former winter settlements of the Arvanitovlachs of Akarnania, which gradually evolved into permanent agricultural and pastoral villages; and he gives much more information about their traditional organisation.[4]

In around 1840, the large Arvanitovlach settlement at Bitsikopoulo was apparently destroyed and abandoned following raids by Arnaut brigands. Most of the families who had been living there since Ali Pasha’s time fled to the safety of the newly established Greek state, where they continued their nomadic pastoral lifestyle, moving between the Agrafa Mountains and other highland areas in Evrytania, and in Epiros too, in Ottoman territory, and the lowland areas of Xiromero in Akarnania as far as the mouth of the Aheloös. Heuzey reports that in 1856 they numbered 800 families (4,000 to 5,000 souls) and established twelve large winter settlements with between fifty and a hundred families each.[1]Between 1865 and 1870, they gradually started to establish more permanent dwellings in these winter abodes. The villages which they established at this time are now the southernmost Vlach settlements: Stratos (Sourovigli or Yannika), Ohthia (Ohtou or Payeïka), Agrambela (Dayanda), Gouriotissa (Katsarou), Paliomanina (Koutsobina), Strongylovouni (Stournari or Gakeïka), and Manina Vlizianon (Kaledzi).[2] It should be noted that the Arvanitovlachs of Roumeli have come to be generally known as Karagounides. According to an article in the periodical Pandora, in about 1856 the Arvanitovlachs of Aitolia and Akarnania numbered about 2,000 and had 100,000 sheep, which gave the Greek state what was then a considerable income of 20,000 drachmas in taxes.[3] Weigand reports that in 1888–9 there were 2,625 souls in the seven former winter settlements of the Arvanitovlachs of Akarnania, which gradually evolved into permanent agricultural and pastoral villages; and he gives much more information about their traditional organisation.[4]

Aravandinos reports that, already in Ali Pasha’s time, some Arvanitovlach groups were settled and cut off in the highlands of Akarnania and Evrytania.[5] It is difficult to know exactly what he means by this laconic observation; unless he is referring to the Vlachs whom Pouqueville found living in a group of villages on the southern slopes of Panaitoliko, on the border between Aitolia and Evrytania, and whom he calls Kossiniot Vlachs or Bomieis. According to Pouqueville’s records, the most important village in this group was Kossina, now Kokkinovryssi, and the Kossiniot Vlachs numbered 1,200 families in all. In 1807, the Vlachs of Kossina and the surrounding villages found themselves at odds with Ali Pasha and were forced out of their homes. After this they headed for Mount Aninos or Iti, and became fully nomadic stockbreeders, dispersing all over eastern Roumeli, from Othri to Parnassos, Elikonas, and Parnitha in Attica.[6] Regarding the population in Attica, Pouqueville distinguishes the settled Arvanites from the Vlachs, pointing out that the Vlachs of Attica were pastoral nomads and their presence there was seasonal. In the winters, some falkaria from the Vlach villages in the Pindos, and also on Parnassos, dispersed beyond the traditional Thessalian winter pastures as far as the lowlands of Viotia and Attica, where they grazed their flocks and sold the woollen goods which they produced in their highland communities.[7]

In 1834, immediately after the birth of the new Greek state, another European traveller, Gustave d’Eichtal, reports the existence of nomadic pastoral Karagounides (Arvanitovlachs) in eastern Roumeli. A falkari was setting up its winter quarters in the area of Atalandi at that time, in connection with which d’Eichtal says something very interesting: he hopes that these Arvanitovlachs will not leave the territory of the fledgling Greek kingdom, but rather use their wealth and labour to help build up the small, poor, newly-independent Greece. He observes that, although they have no inclination towards farming, they could turn their drive and vigour to craft-trades and commerce.[8] In 1852–4, the French traveller Edmond About met pastoral Vlach nomads on the outskirts of Athens and gives quite a vivid account of how these people, who were probably Arvanitovlachs, provided the Athenians with their Easter lambs. He leaves no room for doubt, for he observes that the Vlachs who were living in Attica at this time spoke a corrupt Latinate language.[9] In the same period, François Lenormant also mentions the existence of these, probably Arvanitovlach, nomads in the same areas, and notes that some of them overwintered at Dafni Monastery, just outside Athens.[10]

After the birth of the Greek state, the only major settlement occupied by any considerable number of the Arvanitovlach families who were scattered about eastern Roumeli was Imirbei or Birbili, now Anthili, just outside Lamia. In 1833, the hitherto Turkish-owned çiftlik of Anthili was bought by the Dzallases, a wealthy ethnic Greek family from Vienna with roots in Korçë. Intending to make their newly acquired estate productive, the Dzallases invited share-croppers to settle and work in the then uninhabited çiftlik of Anthili. Shortly after 1850, a group of some fifty Arvanitovlach families settled alongside the few Greek-speaking and motley share-croppers. They had previously tried to establish a new permanent settlement at Vardari near Mendenitsa. According to local traditions, one reason why they settled en masse in Anthili was the fact that the Dzallases were also Vlach-speakers. The Arvanitovlachs of Anthili gradually became farmers and stockbreeders, though for several decades they retained a summer settlement at Liathitsa near Damasta Monastery on the slopes of Kallidromo. Smaller groups of Arvanitovlach families, offshoots of the Anthili families, settled in Mendenitsa, Molos, and Exarhos.[11]

We cannot be absolutely certain whether the Arvanitovlachs of Anthili and eastern Roumeli in general were all descended from the Vlachs of Kossina or whether their ancestry lay with Arvanitovlachs who, like those of Aitolia and Akarnania, entered Greek territory then or were already there. There are indications, certainly, that some of them at least were already in Roumeli before the Greek War of Independence broke out. In 1851, an Arvanitovlach falkari established a summer hut settlement at Voboka on the southern slopes of Othri, near the village of Pelasyia and what was then the frontier. In a conversation with Theodoros Yennaiou Kolokotronis (Theodoros Kolokotronis’s young grandson), the falkari’s aged tselingas, whose name was Poulios, claimed to have been a companion of Konstandis and Theodoros Kolokotronis and a friend of Odysseas Androutsos.[12] This supports Aravandinos’s view that there were Arvanitovlachs in Roumeli long before 1821, and it also, perhaps, bears out what Pouqueville says about the Vlachs from Kossina.

When Henri Belle travelled through almost the whole of what was then Greece between 1861 and 1874, he reports that the total number of Vlachs living in Roumeli, and principally in Akarnania, the Agrafa, and on Iti, was around 12,000.[13] So it is clear that, during the nineteenth century a considerable number of Vlachs, more specifically Arvanitovlachs, were gradually assimilated in towns and villages over almost all of Roumeli, and became an integral part of the population of the new and still tiny Greek state. Even more interesting is Cousinery’s reference in 1831 to the presence of Vlach-speakers, probably Arvanitovlachs, in the area of Argos in the Peloponnese. He reports that, after the War of Independence of 1821, he met some Vlachs, men and women, in Argos market, who told him that they were pastoral nomads with settlements in the mountains around Argos. He also notes that these Vlachs spoke a Latinate language, like the Vlachs he had met in Macedonia.[14]

Certainly, these were not the only Vlach groups which made up the population of Roumeli. If what Pouqueville says even partially reflects the facts, then we must also take into account some other groups of Vlachs, who were already permanently settled in a large number of villages in Roumeli in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. He calls them ‘Bouii’, and they may probably be identified as the Bouii found in earlier writings. He notes that they lived in three discrete groups of settlements, and that a large segment was already at an advanced stage of assimilation. These groups of Vlach settlements were: i) around Ypati on the north-western slopes of Iti;[15] ii) south and south-east of Karpenissi;[16] and iii) probably north of Lamia, on the slopes of Othri, near the Fourka pass.[17] Pouqueville estimated their total number, together with some pastoral nomads of the same provenance, at about 11,000.[18] We may consider that the semi-nomadic inhabitants of the village of Stavropiyi in Evrytania (known as ‘Ablianite Vlachs’, from the old name of the village, Abliani) were descended from them. By the beginning of the twentieth century, the Ablianites appear to have been exclusively Greek-speaking, with no memory of having known or used any other language, though they faithfully observed the transhumant Vlach lifestyle. In the winter, some of them went down to Evinohori at the mouth of the River Evinos near Messolongi, and others to Lamia.[19] However, questions still remain: were these population groups once Vlach-speakers? When did they settle in Roumeli? And what eventually became of them? The most likely answer is that the Arvanitovlachs who were in Roumeli when the Greek state came into being, or shortly afterwards, had no direct or close connection with Pouqueville’s Bouii. The Bouii were probably part of the Vlach population of the Great Vlachia of the Middle Ages. But more exhaustive research is certainly required if these questions are to be answered more clearly.[20]